Come celebrate the Grand Opening of Seasoned Vegan

55 Saint Nicholas Avenue, Harlem, NY 10026

Saturday, May 3 | Ribbon Cutting at 2pm

Self-taught African Teen Wows M.I.T.

Young Kelvin Doe A.K.A DJ focus of Sierra Leone makes MIT technology look like child-play. Kelvin shows us that ramshackle materials may be pieced together to create “low-tech” solutions to “high-tech” problems; however, the sophistication of certain sciences makes such efforts seem unattainable. Stuff like this makes it all worth it. Thoughts?

More at crowdrise.com!

Seasoned Vegan Restaurant

A design idea to be realized in Harlem. More at Blacklines of Design Inc. Thoughts?

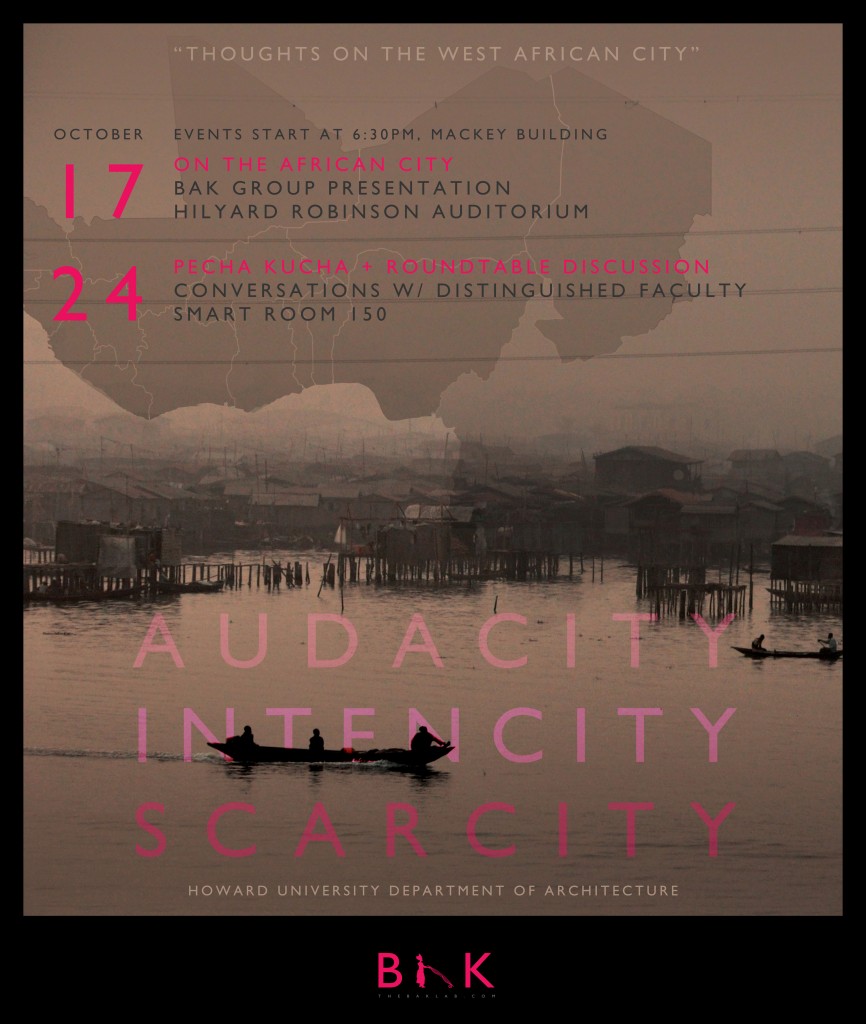

#BAK TALK /// THOUGHTS ON THE WEST AFRICAN CITY LECTURE SERIES

Unmasking A Festival Part I

An art festival is a marathon of creative stimulation. It is a competition that brings the titans of the art industry into one arena with the goal of competing for the ultimate title of the most desired or talked about collection. It is a multi-day battle to determine what will be perceived as the best, the most sought after, exceptional, intricate, and personal pieces from a select group of artists. Like animals in the wild the collector scans the room for prey and all is fair in this friendly contention that masquerades as a celebration. Perhaps the most eloquent representation of the art marathon is the Art Basel Miami. The Art Basel is one of the many large-scaled annual festivals held within the first world. The celebration wouldn’t be complete without a vast array of pieces. It is significant that the large quantity to vie for also includes selections that often have origins in the developing world. If this is how the first world celebrates, what then is the format for the developing world? In a word, FESTAC was born in response to this very question. In Africa, a continent composed of several developing countries FESTAC 1977 became the answer to how an art marathon or unity celebration could occur in a developing nation. Largely considered the “last significant art event” on the continent the festival was both a celebration and a much-needed conversation between divided nations. The events that led to the festival and the resulting legacy tell a different story of what an art festival can become and manage to achieve.

Although it manifested as a revolutionary event, FESTAC 1977 wasn’t the first African Art Festival. It was in fact the second and followed Dakar’s Pan African art festival. In 1966 Dakar, one of the most developed cities in Africa at the time, hosted the celebration to bring together the Pan African art world and engage the public in a much needed dialogue. Featuring everything from poetry to dance the festival was meant to be the first in a series that would occur every four years and showcase the best art of the moment. The event’s success and momentum led Nigeria to submit a proposal to host the event four years later. Four years came and went without seeing the next festival. Ten years after Nigeria’s independence the country was looking for an event to solidify its stability. The festival was meant to be a spectacle but was stalled for seven additional years past the planned date due to political problems and war surrounding West Africa. With the passage of time and many cancellations some doubted the festivities would ever occur. Meanwhile Lagos used this time to build facilities that could compete with Dakar and create the promised unprecedented exhibition for the continent. Funded largely as a result of the recent oil boom in Nigeria, the construction was a part of a city wide overhaul. The preparations included new roads designed by German engineer Julius Berger and a resulted in a denser city center. The stadium, a well-constructed cylinder, expands like a crown to the sky and became the centerpiece for the town and holds a place as the highest point within the community. After seeing a similar stadium in Bulgaria, the Nigerian president, General Yakubu decided that the city of Lagos needed the exact same stadium to host the upcoming event. He was able to attain an even larger facility that would res Gowon emble the general’s cap during the recent war. It is proudly regarded as an African architectural symbol. Ironically, the stadium is in fact a result of European industrialism and Bulgarian craftsmanship. The resulting stadium is a strange choice for an African Art festival but nonetheless a majestic result that accommodated and legitimized the event.

-AyoBak

Scrambled Eggs?

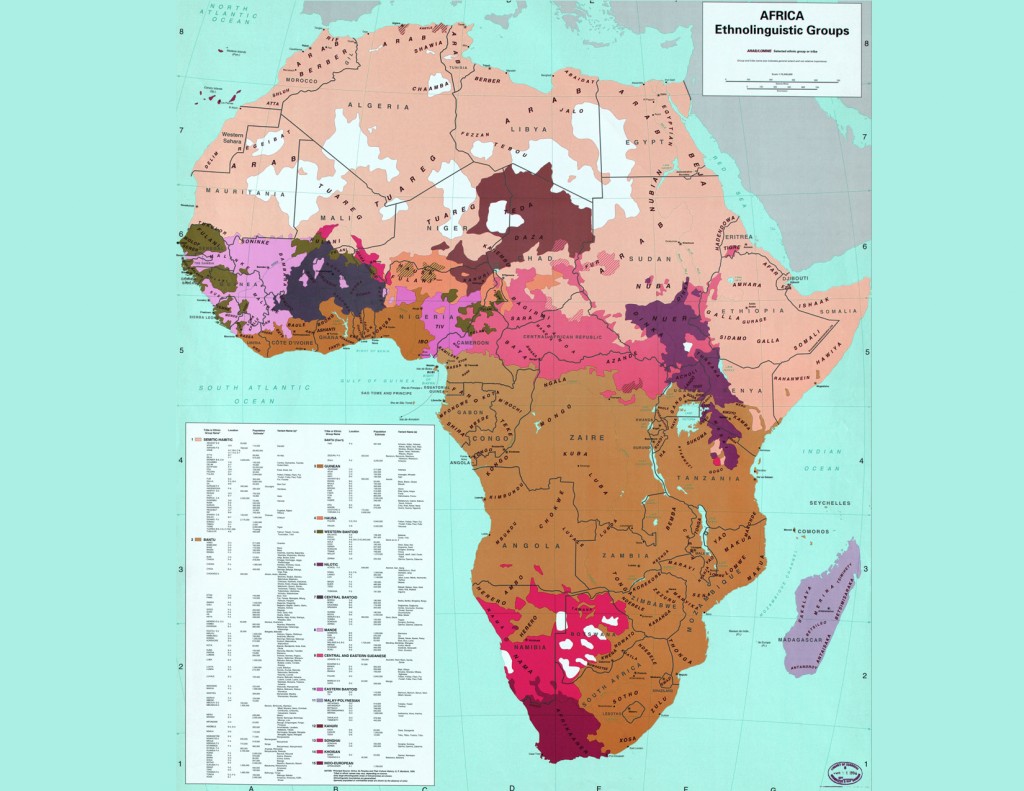

Is discordance in the sub-regional contexts of the African continent exacerbated by its ethno-linguistic diversity? Somehow it seems Africa drew the short straw atop the proverbial Tower of Babel; though language is perhaps the most pervasive purveyor of ideas, customs, values and beliefs, its microcosmic assortment in the different African sub regions seems to leave confusion in its wake.

Beg that I might not be mistaken- ethno-linguistic diversities are a great treasure on the continent and are (and were) perhaps necessary, as safety lines, in navigating the harsh spatio-economic climates on many parts of the continent. But, these lines continue to be exploited as avenues of conflict in sub regional affairs. They become the loci of fissures so deep that cooperation is fragile or near impossible in many continental dialogues.

What am I really trying to bite at? The questions- though the rhythms and tones of different African sub-regional spoken languages sound vastly variegated, how different are the ideas they carry? If they exist, what are the thoughts that ferry across clans, tribes and peoples? Can we define them?

I admit that identifying or defining an Ortgeist- spirit of place- may not prevent conflict, but perhaps it could aid the continent in taking a stand against pressure from within and without; from the West and more forebodingly, the East. Perhaps the reeling blow of ‘the scramble for Africa’ need not occur again in the course of China-Africa relations- perhaps.

DayoBAK